I had so many questions about the character of the Queen in Donizetti’s opera L’assedio di Calais. Firstly, her name. King Edward III was married to Philippa. In Salvatore Cammarano’s libretto, her name is changed to Isabella (who in reality was Edward’s mother). Why? Instead of looking at a primary source for the history of the Siege of Calais, such as Jean Froissart’s chronicles, Cammarano copied two of his contemporaries, Luigi Marchionni and Luigi Henry, who had created popular drama and ballet interpretations.

Marchionni’s play opened on the name day of his patron, Maria Isabella, Queen of Naples and Sicily, so there’s not a lot of mystery as to why he preferred Edward’s mother’s name. The two queens, however, couldn’t have been further apart in character and reputation.

Maria Isabella, Infanta of Spain by Goya, 1800

Maria Isabella was the youngest daughter of King Carlos IV of Spain and at the tender age of 12, her mother offered her hand in marriage to Napoleon (who was 32 and married to Josephine at time). Although his advisors wished him to divorce and marry a royal, he scoffed and reportedly said, “If I would have to remarry, I wouldn’t look in a house in ruins for my descendants”. Stinging from this rejection, her mother arranged another match, this time to her cousin, the nephew of Marie Antoinette and Louis XVI, Prince Francesco of Naples and Sicily. Naples was an ally of England at the time and it was hoped that this match would forge a deeper bond to Spain’s ally, France. At the age of 13, she was married to her 25 year old cousin. Her mother-in-law, Queen Maria Carolina, who was Austrian and against the alliance with the French, wrote this of her:

“A fine, fresh, healthy face, not Bourbon in the least, but white and red, with black eyes. She is very stout and sturdy, yet her legs are very short. So much for her exterior. The rest cannot be described because I myself cannot understand it. She is null in every respect, knowledge, ideas, curiosity. Nothing, absolutely nothing. She speaks a little Spanish but neither Italian nor French, and only monosyllables, Yes or No, indiscriminately. She smiles all the time, whether she is pleased or not…Francis’s child aged four has far more intelligence. Francis has engaged masters to teach her Italian and the rudiments of geography and arithmetic. She knows nothing except a little piano. I have tried to praise and enliven her. She feels nothing; she laughs. She is an automaton which might acquire certain attitudes but never real maturity. Were I the ambitious, intriguing woman I am said to be, I should be enchanted to have such a daughter in law who will never become anything, but I am too conscientious for that. I tried every means to mold her as a companion for her husband, even if this may turn her against myself. Believe me this child is a tight present, for she will neither ennoble nor improve our race. All the numerous Spanish clique, all their projects and schemes, have received a knockout blow by the arrival of this Princess and her perfect nullity.”

Did I mention that Maria Carolina was rather fond of her recently deceased niece, who happened to have been married to Prince Francesco before Maria Isabella was dropped on her doorstep?

Family of King Francesco I (Maria Isabella is seated in the black dress)

Regardless of her lack of personality (or intellect or beauty) she did have passion. Francesco and Maria Isabella had 12 children together. (Her first was born when she was just 15!) When he died in 1830, the flirtatious Maria Isabella was determined to remarry and chose another Francesco, Count dal Balzo dei Duchi di Presenzano, a handsome young lieutenant from an ancient but impoverished noble family. (She was 50 and he 34 when they wed).

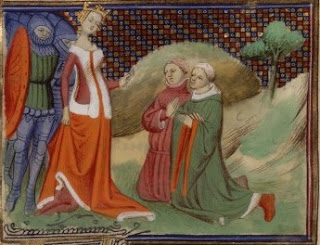

The marriage of Isabella of France and Edward II, Flemish manuscript, c.1470

In contrast, The She-Wolf of France (as Queen Isabella of England was known) was well respected for her diplomatic skills, intelligence, and beauty. The only daughter of King Philip IV of France, Isabella was married to Edward II when she was 12 and he was 24. Although they had four children together, Edward preferred the company of his male favorites. (He chose to sit with one of them, Gaveston, rather than her at their wedding banquet!) Isabella understood the game of politics and supported her husband until Gaveston was murdered. After that, her husband befriended Hugh Despenser, who confiscated all of her English lands, imprisoned her French staff, and had her youngest children placed into his family’s custody. By 1325, she fled to France to plead her case to her brother, King Charles IV. She began an affair with Roger Mortimer, the earl who had led a failed revolt against Edward in 1322.

Return of Isabella to England with her son, Edward

She raised an army, invaded England, and quickly seized power of the realm.

Isabella executing her husband’s lover, Hugh Despenser

She had Despenser executed and forced her husband to abdicate to their son, 14 year old Edward III. After having moved her husband to a remote Welsh castle, he mysteriously died from a “fatal accident”. She and her lover Mortimer successfully ruled England for four years, acquiring vast sums of money and land, until Edward III demanded he ruled for himself when he was 17.

(A fun read is Queen Isabella: Treachery, Adultery, and Murder in Medieval England by Alison Weir)

Philippa of Hainault crowned Queen of England

Philippa of Hainault was no slacker, either. Her mother was Isabella’s cousin and the two noblewomen arranged the marriage between Philippa and the future King Edward III in 1326 when she was just 12. (Isabella used Philippa’s dowry to pay the mercenary soldiers who helped her invade England.) At age 16, when she was six months pregnant, she was crowned queen of England (Isabella didn’t want to share her title, so had her coronation delayed for two years). She and Edward had 13 children and traveled often together.

While he and most of the troops were away fighting in France in 1346, she ruled the kingdom. On horseback, she successfully rallied the remaining English soldiers to squelch a Scottish rebellion, as recounted by Henry V in Shakespeare’s famous play:

For you shall read that my great-grandfather

Never went with his forces into France

But that the Scot on his unfurnish’d kingdom

Came pouring, like the tide into a breach,

With ample and brim fullness of his force;

Galling the gleaned land with hot essays,

Girding with grievous siege castles and towns;

That England, being empty of defence,

Hath shook and trembled at the ill neighbourhood.

Philippa of Hainault triumphant at the battle of Neville’s Cross, 1346

Both the play and ballet had been based on a play written in in 1822, Le Siège de Calais by Philippe-Jacques Laroche, which in turn was based on a play written in 1765 by a French aristocrat turned rebel actor named Pierre Laurent Buirette de Belloy. If Cammarano had read this earlier play, he would have learned about the queen’s name discrepancy. In the original script, there are 23 pages of historical notes, in which Belloy states: “The wife of Edward, whom some historians call Philippa, and others call Isabella. Perhaps she had two names. I have chosen the better and obviously the one that comes from the name Philippe, the one that can only be the daughter of the Count of Hainault, and niece of the King of France.” (You can read the original 1765 script by clicking here)

Belloy also answers two of my other questions: why is the queen so irritable in this libretto? What motivates her to plead with the king to spare the lives of the Burghers of Calais? He translates his reading of Froissard’s account:

“The Queen of England, who was pregnant, got on her knees and cried: Ah! Gentle Sire, since I have returned in great peril across the sea, I have asked you nothing: but pray you humbly as a gift for the Son of St. Mary, and for the love of me, please show these six men mercy. The King looked at her, and paused for a moment, and said to her. Ah! Madam, I would rather that you were elsewhere than here: but you plead to me so that I cannot refuse you. The queen took them to her apartment, had them take off the ropes around their necks, and bade them sit and dine at their leisure. Then she gave to each of the six nobles golden crowns, and conducted them out of the camp in safety.”

This made her testy first lines and her complete switch to compassion by the finale so much more understandable for me. She’s pregnant and has just fought and won a campaign on horseback for him in Scotland. She undertook a perilous voyage by boat to Calais, and expected to sleep in a comfy bed in the palace inside the city, as he had promised. Instead, she arrives and is greeted by soldiers who escort her to a war-torn army tent. When she sees Eleanor plead for the life of her husband for the sake of their son, the queen is moved not only by empathy for a fellow mother, but also because she doesn’t want this brutal act of her husband’s to bring about a bad omen for their unborn child.

Queen Philippa with Edward III and their son, Edward the Black Prince

My costume design sketch for the queen: